Past Exhibition

The Irony of Capacity: A Dark, Black Comedy

Dawaun’s latest body of work offers an array of quotidian abstractions in sculpture, and trials of look-alike jokes via portraiture.

Words fail, and then the fun begins.

In his solo show at Hamiltonian Artists, Kyrae Dawaun tightly weaves concept, narrative, craft, and form into a river-of-consciousness whole, the effect of which is at once exhilarating and deeply moving.

One can enter a river bodily, with the risk that entails; ride atop in watercraft, close but still apart; or walk along the bank, taking in the river’s course and surrounding land. Similarly, viewers can engage with Dawaun’s intimately scaled paintings and sculptures in myriad ways: through language, character, and narrative; as an assertive celebration of painting; as a demonstration of formal rigor; and more.

I have the good fortune to be already familiar with Dawaun’s work, having seen a smaller solo show two years ago; his combination of narrative figure painting and abstract floor-placed sculpture was immediately intriguing. It is gratifying to see how that blend has evolved into the finely honed vision presented here.

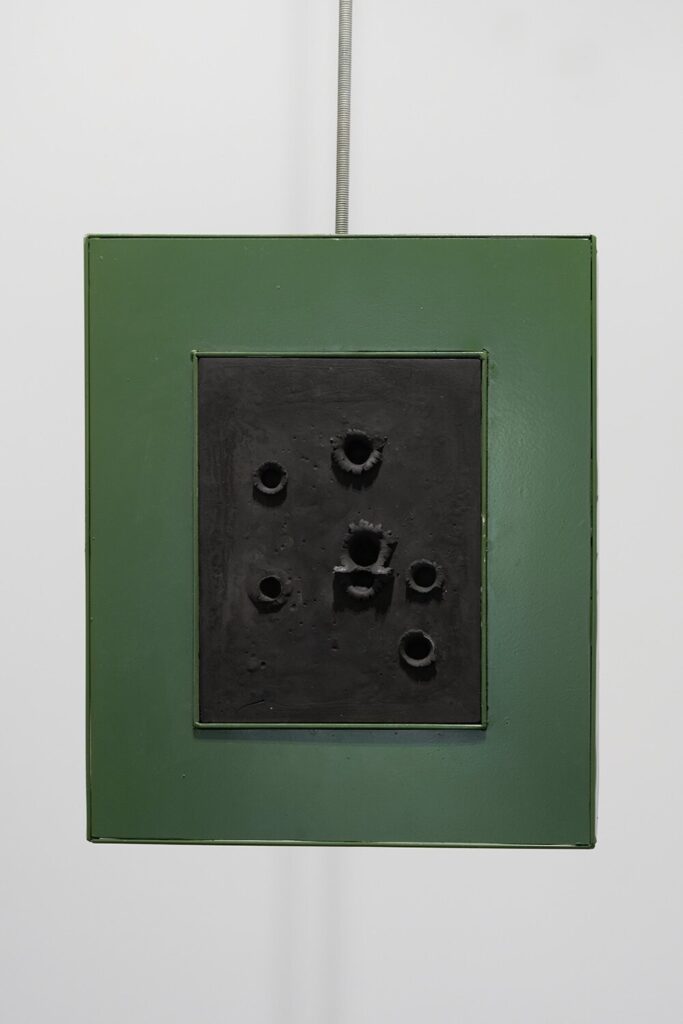

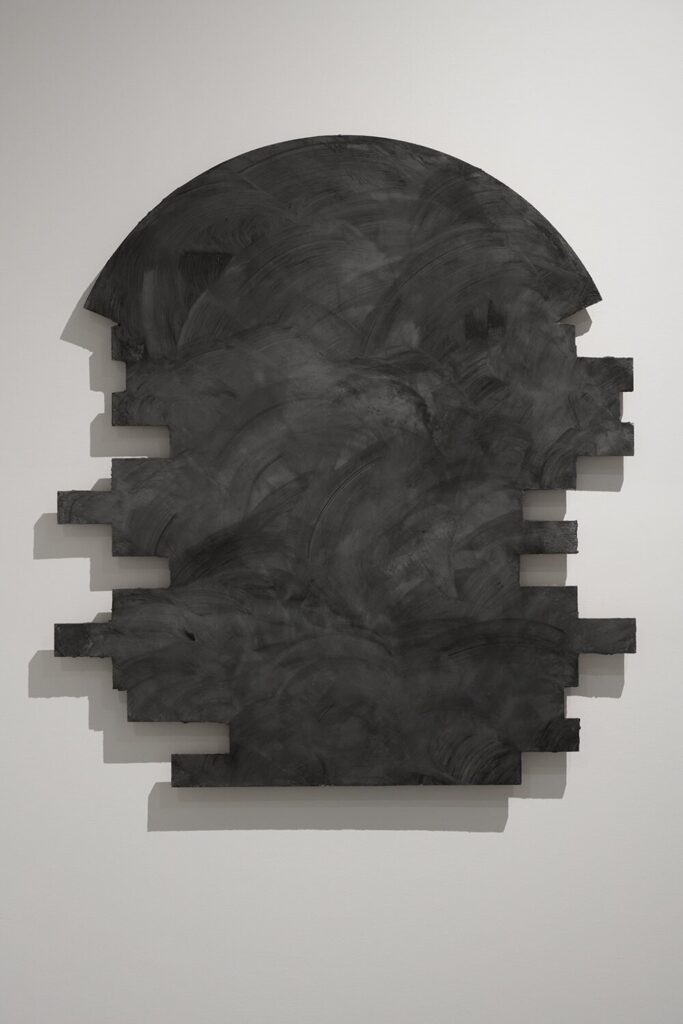

In Irony of Capacity, sculpture works as a shaping and guiding element in Hamiltonian Artists’ long, relatively narrow space. Work is again placed on the floor but is also wall-mounted at various heights as well as suspended. On entering the gallery, the viewer is greeted by a small anteroom created with the help of a moveable wall. In this area are the suspended work, the mysteriously handsome booked (marring) (2023), and the first piece encountered, hole in the wall (seasonal maintenance) (2023), facing us edge-on. As in the other hole in the wall pieces, the unfinished wood edge lends a rough-hewn note, evidence of Dawaun’s stated desire to “let the seams show.” The wood-panel paintings, ranging from 23 × 22 to 8 × 10 inches, are nearly three inches deep, making the more diminutive ones feel like sculptures themselves: small slabs with amazing pictures on top. Hung in proximity to wall-hung 3D work—all of which also feature ninety-degree angles—the paintings become even more a part the show’s dimensional landscape.

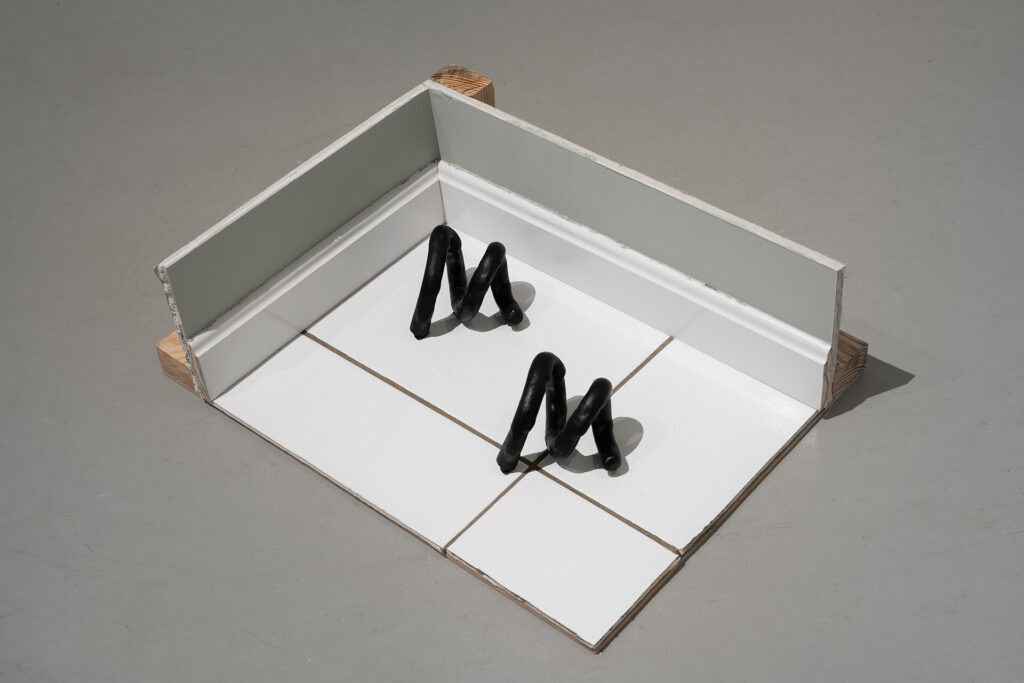

The small floor pieces have a curious quality of scale, seeming like microscopic versions of exponentially larger structures. At the previous show, I mentioned to the artist that viewers would have to crouch to fully appreciate the work; he responded that his intent was to influence how we interact with the gallery space. At Hamiltonian, we encounter coil (a gathering) (2023), a small floor-mounted piece made with ceramic tile, wood, gypsum, and cement. Wooden boards abut the outer edges, and lengths of baseboard form two sides and a corner. All quite ordinary, except for the black tube shapes extruding from the floor. Are they beings from another dimensional universe, come to visit our bathroom? If we crouch to view more closely, maybe we can get to know them, make a new, small friend of this artwork. Or, in a scale-flip, are we instead impossibly large giants gazing down at the arena of battle between two huge, black sandworms (oil-worms?). What do these perceptual scales say about the imagined size of the gallery itself?

Moving down to the level of the work, obeying its gentle spatial imperative, can have a spiritual aspect as well. In many world cultures, lowering the body—whether by bowing, genuflecting, or prostrating—is seen as an act of respect, humility, or worship. This change of physical posture, meeting the work where it is, can elicit a deeper level of emotional engagement, particularly in the spiritually and aesthetically rich context of this show.

Light moves through the work in beautiful ways, literal and figurative. In the wall sculpture hole in the wall (seasonal maintenance) [peach pit black / summer] (2023), rectangular side projections create shadows that play the room light like an instrument. Gestural brushstrokes create a lovely glow in the top center of the 45-inch-tall piece.

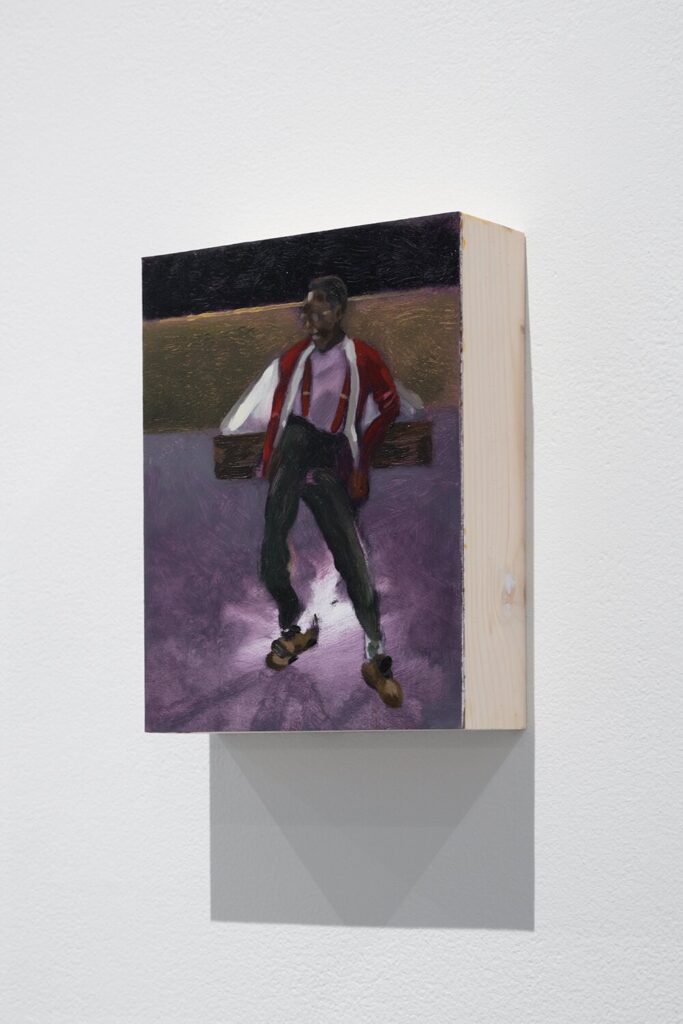

Light works in symbolic ways as well. In ressembler (Urkel) (2023), the quintessential nerd character Steve Urkel from the ’90s Black sitcom Family Matters (1989) seems to strike lightning with his right heel, perhaps while doing his stereotypical dance. The figure is centered against what looks like a runway in the background, the colors dark and acidic. Here the light implies power; the comic foil to Black-TV masculinity is redeemed as a sort of skinny danger-shaman.

A more metaphoric kind of light was also at work, in the form of the artist’s frequent and engaged presence at the gallery. Dawaun was in the space on perhaps three of my four or five visits. On one such occasion, the artist offered homemade raisins, saying he wanted to show that “we can make things; we can do things.” This message resonates powerfully in an era where the handmade is encountered less and less. On my next visit, faux, painted boxes of raisins had appeared on the previously bare top of hole in the wall (seasonal maintenance)—their labels spelling out “not from concentrate”—and raisins were available for snacking.

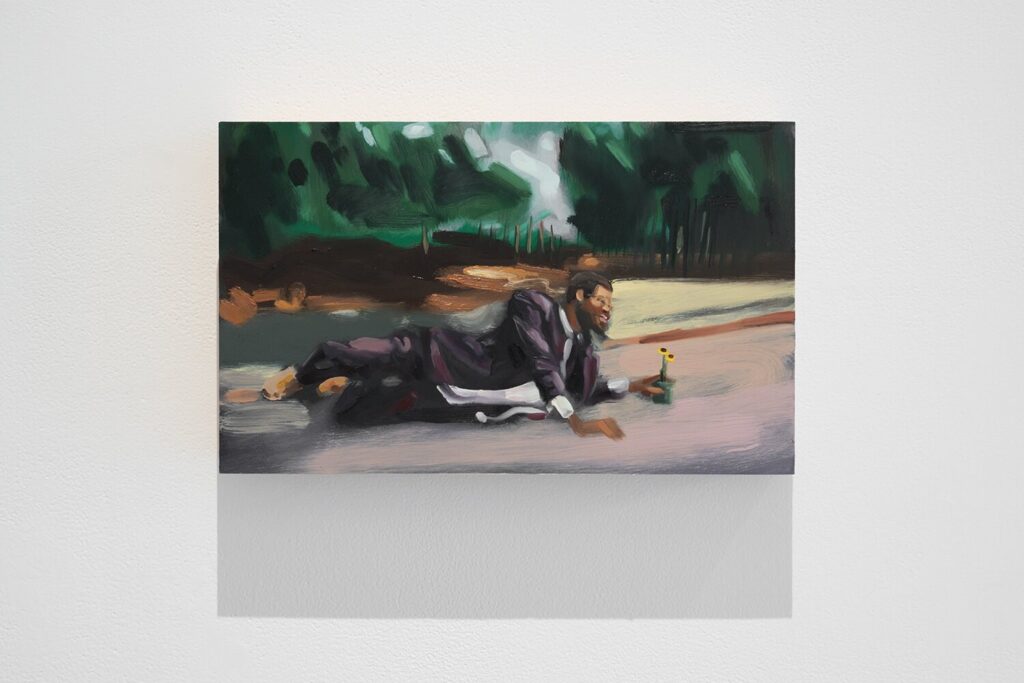

The show feels suffused with tenderness, perhaps most strikingly in the beautifully elegiac [crawl] Pope L (2023). Made more poignant by the subject’s recent death, the painting depicts the multidisciplinary artist performing a signature crawl work How Much is that Nigger in the Window a.k.a. Tompkins Square Crawl (1991), in which he traversed the perimeter of Tompkins Square Park on his stomach. The light is cinematic, haunting, and the stumps of ghostly trees populate the center of the image. Pope.L’s right hand is painted in delicate, wispy strokes, at the end of a ramrod-straight arm; set against pavement rendered in pale lavender, they give the scene a feeling of tragic sweetness coupled with incredible determination.

There’s tenderness, too, in the artist’s hand. The paint application ranges from diluted and brushy, to flat and brushless, to glossy alla prima dabs, and each technique has a different sense of light and emotional space. In ressembler (urquelle) (2023), the Urkel character’s cool alter ego dances in a white suit under club light. The left pant leg dissolves in a brush stroke that softly shows the path of the bristles, enhancing the work’s dreamlike feel. The flatter brushwork of ressembler (Ché) (2023) seems to cast the figure in daylight vivid and declarative. The more broken brushstrokes of ressembler (Martin) (2023) and ressembler (Ocean) (2023) reflect light in a way that seems to animate the subjects’ faces. This dappled light set against the soft, dark backgrounds gave me the uncanny sensation that my gaze was illuminating the piece as I approached to view more closely.

Not all is warmth, however; weirdness and tension are by no means absent. For example, what to make of natural gas, in which a woman’s hands hold up to a radiantly beatific light what looks like a travel-size jar of Vaseline? The hands are gently splayed, the right pinkie glowing like a beacon; their posture projects a sense of reverence, but to what—petroleum jelly, intrepid foe of ashy knees and chapped lips? A seeming counterpart piece, pitched hands, is no less enigmatic. At first glance, it looks like one of those mass-produced praying-hands wall plaques. But here only the fingertips touch, suggesting the stereotypical contemplative pose favored by B-movie villains. Maybe that explains the apparent coating of molten metal?

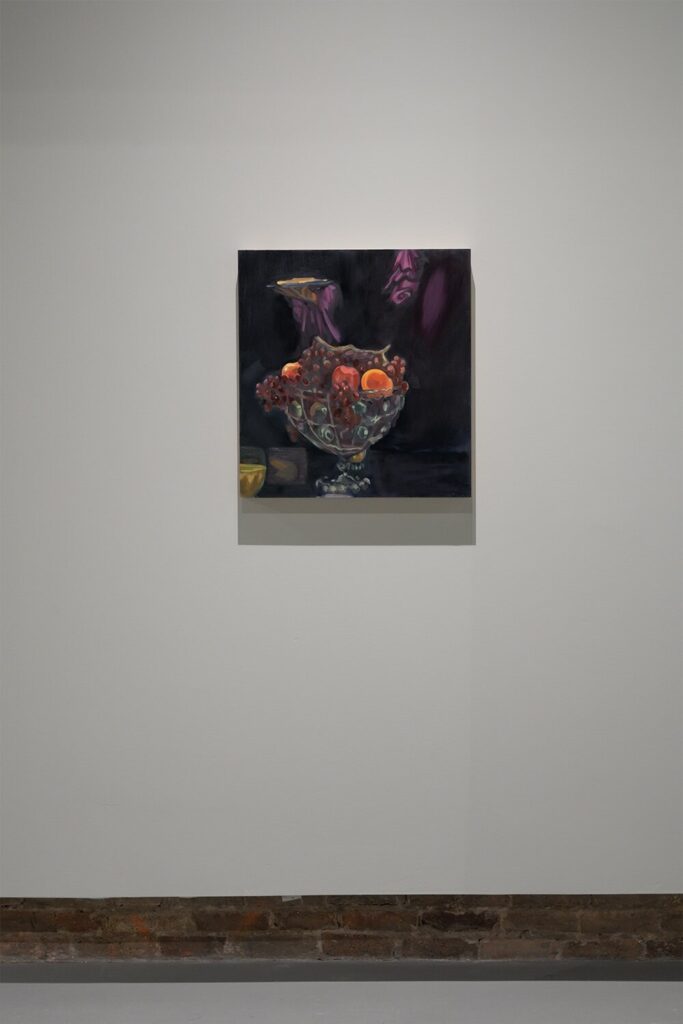

Some tension is more formal in origin. The floral still life of a few lilies (above our heads) (2023)—alluding to Black gay literary icons Bruce Nugent (Smoke, Lilies and Jade [1926]) and James Baldwin (Just Above My Head [1979])—is a bit unsettling. The vases are cans, beer bottles, and a bleach bottle containing a suspiciously yellow liquid. The titular lilies (one calla, one Easter) poke awkwardly toward the top right corner; the overall effect is restless and unquiet. Its dark twin, table grapes (2023), is equally off-kilter. The composition pushes tightly to the left, the colors lurid in the dark space. Objects that seem unconnected to consensual daily reality float in the top half of the image.

My usual approach to art looking, as attested by my little first sentence above, is to avoid the attendant words and look first (sometimes only) at the work. Fortunately for me, that was impossible in this case. That doesn’t mean I understood all the words, but I realized that a one-to-one mapping of language to concept wasn’t necessary to know what was being expressed. That said, I did think about possible meanings for “ressembler”: one who both resembles and dissembles? The use of the coined word together with familiar characters, some fictional, some real, provides a modular kind of narrative, an idea structure for viewers to move through.

After seeing shows that are (or purport to be) about identity, one can sometimes leave, feeling bereft of insight or inspiration. Not so here. One sentence in the artist statement reads as both a salutation and a cry: “The inevitable stranger, the dark one, the black American, oh the beauty of what I could be.” I, not we. This subjectivity is crucial and liberatory. Dawaun goes on to tell us that the show “serves as a spatially engaged play on language . . . [contemplating] black as it is used in a great expanse of meaning.” This sense of expansion, along with the generosity and community shown by the artist, informs the show and powerfully activates the viewer’s experience.

Gravity is the heart of a river’s power; it cuts through the land, establishing its presence, at times with breathtaking beauty. Get close enough and you might find yourself in the water, perhaps swept away. In this blackly comic river of consciousness, that is a truly wonderful thing.

Wayson R. Jones is an artist.

Past Exhibition

Dawaun’s latest body of work offers an array of quotidian abstractions in sculpture, and trials of look-alike jokes via portraiture.