Past Exhibition

Pale Grass Blue

Misha Ilin’s body of work asserts that ecocide, wars, body politics, and capital each exist as a sort of radioactive event, altering the genome of “reality.”…

Misha Ilin’s exhibition Pale Grass Blue at Hamiltonian Artists in Washington, DC, is an installation of interrelated works that radiate outwards from the back of the gallery. There, the viewer is greeted by lead pig (one day this sadness will fossilize) (2024), a floor-to-ceiling assemblage. A pig-shaped cookie jar containing a chunk of uranium ore sits on a warped foil square, an ashen disco ball suspended from above. The lid is slid open slightly, and a microphone on a boom stand pointing into the crack gives the impression that the little gray pig, bathed in a bluish spotlight, is performing—the uncanny tick-tick-tick of a Geiger counter is its eerie, repetitive refrain.

Like the uranium’s half-life, the show’s artworks seem to fall off from this sculptural hyperobject. In hello red forest, hello soil (2024), Ilin has assembled plastic toy soldiers in piles of sand nearby. They embody the Russian soldiers who dug themselves into trenches in the exclusion zone near Chernobyl during the invasion of Ukraine. Perhaps the latent toxicity of the ground was a more certain threat to the soldiers than the Ukrainian resistance, but time will tell. It is said that another 10,000 years will pass before Chernobyl is safe enough for human habitation. It is said that the green tree frogs there have changed color but still survive. How habitable is this gallery, uranium chattering away from inside the pig’s belly? According to the artist, the fall-off zone measures a few inches. But it doesn’t feel safe, even looking from a distance. The disfigured soldiers’ melted, colorless, and congealed bodies signal an inexorable, inevitable decay.

Ilin was born in Russia in 1985, a year before the meltdown of the reactors at Chernobyl. The worst nuclear disaster in human history, then, could be seen as the artist’s political primal scene. He was born into a historical inflection point of human-made ecocide and grew up alongside the resulting mutations, organic and social. The artist seems to feel a kinship with the genetically altered; the pale grass blue butterfly, referred to in the exhibition’s title, was mutated due to the radiation at Fukushima. Low, bluish light illuminating the exhibition references both the color of these mutant insects and the altering power of radioactive materials. On several assemblages and paintings, made of plaster sprayed with silvery chrome paint, seemingly coated with ash, Ilin places replicas of these butterflies; prefabricated, ordered from Amazon. In the haunting scene of vanitas (table series) (2024), what looks like a deserted dinner table serves as a landing pad for these post-apocalyptic creatures. Eerily still and frozen in time, what could be a sign of life’s persistence in the wake of destruction becomes an inert specimen, stultified in media res on a tableau mort.

Throughout the exhibition, didactics offer instructions. To the right of (epigraph instruction or how to view unshielded radioactive specimen in the gallery) (2024), an embedded text reads:

“The Gallery was instructed to comply with the following radiation safety standards: US NRC (10 CFR Part 20), OSHA (29 CFR 1910.1096), and IAEA GSR Part 3.

Samples of uranium ore and caesium-137 were instructed to be obtained in accordance with US NRC (10 CFR Part 40) and NYSDOH (10 NYCRR Part 16 and 12 NYCRR Part 38).

Safety measures that were instructed to be taken include indicating sufficient distance from unshielded radioactive specimens…”

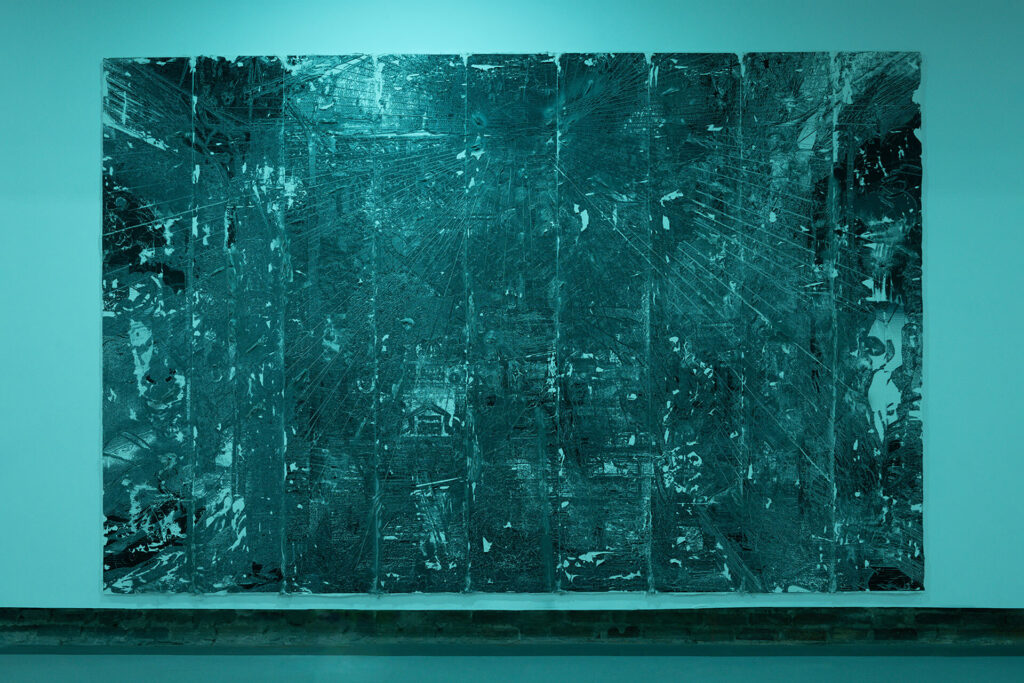

Ilin’s previous projects have often played with the ludic overlap between the rules of games and the regulations of institutions. In this exhibition, the instructions offer cold comfort, exemplifying the distancing of bureaucratic language in the face of imminent danger. Still, there is something playful at play. Wall pieces like the room (2023) offer an interface through which to view a ruined horizon, a fossilization of the screen view of military drone operators, and, in turn, their simulacra in first-person video games.

I am reminded of how often young boys (in particular, though not exclusively) are trained to think of themselves as potential combatants through action figures. In the US, we had GI Joe. I am reminded of the way that I, as a kid growing up in 1980s California, was made aware of the nuclear threat as a science-fictionalized doomsday scenario through anti-Soviet propaganda like the campy 1983 film The Day After, in video games like Missile Command (1980), and post-perestroika superhero stories from Marvel Comics’ 2099 series. Allow me to digress:

Exploding from underwater suspended animation in the year 2099, the Marvel Comics villain Chernobyl has questions.“What place is this? It is clearly not the submarine, but I have been revived, nevertheless! Has the world flung itself headlong into war? Speak! Tell me what has happened here or suffer at the hands of Chernobyl, Knight of the Soviet People!” With flowing black hair, white eyes, a hammer and sickle motif adorning militaristic shoulder pads and belt buckle, the imposing figure’s confused queries are made all the more intimidating by the fact that he speaks without a mouth (or nose, and in Russian, as a note on the page helpfully points out.) Chernobyl’s entrance panel shows him strangling a man in a gray business suit.

“An American? An American!!” The conceit of the Marvel Comics series Spider-Man 2099 is that it takes place after “the Corporate Wars,” its mise en scéne, Nueva York, a megalopolis run by biochemical company Alchemax, known for its commercialization of genetic mutation. The ambiance of Spider-Man 2099 (which ran for 50 issues from 1992 to 1996) is a loud mix of environmental collapse and virtual reality addiction, with daily skirmishes between private security forces and urban guerrillas. Miguel O’Hara, who works by day at Alchemax and by night as Spider-Man, fighting against his corporate overlords, finds himself in a bemused conflict with Chernobyl. The Knight of the Soviet People is a relic from long ago, he represents a political struggle no longer in play.

When Spider-Man (whose powers resulted from a corporate-funded genetic experiment using a copy of the original Spider-Man’s DNA) meets Chernobyl, he taunts him, “Do they have anything like THIS back on the old agricultural collective?” When Chernobyl’s exoskeleton is torn in a fight, his face is revealed to be handsome and anguished. The broken seal risks destroying all of Earth, as Chernobyl is inherently radioactive. The ambivalent supervillain flies off into space, choosing to sacrifice himself rather than destroy the world.1

Chernobyl is factual—what happened there, real, yet the mythologies around radioactive super-powers (whether superheroes or nation-states) are just that: politicized fabrications anthropomorphizing power struggles in a no-win situation, the effects of which are felt by humans, animals, even the inanimate. Back to Ilin’s toy soldiers, then. The half-buried figures in Ilin’s sandbox look like the relics of a kid’s afternoon after a bomb went off. Ilin’s work echoes these speculative fantasies while confronting the viewer with warfare’s high stakes and lived consequences, its toxic aura eating away at us even from a distance. Pale Grass Blue renders The Cold War Spider-Man 2099 figured a curiosity of the past as a kind of cultural exclusion zone that persists in the everyday, our lives and our deaths.

In one of the exhibition’s most emotionally engaging and challenging pieces, the artist asks us not to speculate but to witness. Hanging in strips from the ceiling, casting blue-tinted shadows from the wall, the text-piece (caring instruction or how to handle a radioactive event when the state decided to lie about it) (2024) reveals witness accounts of the events of the Russia-Ukraine war.

The plaster-coated, bandage-like scrolls at once recall casts for broken limbs and the endless scroll of a social media thread. A fragment of one reads,

“It was impossible to stay and listen to bombers flying low over the house. The sound they make is terrifying. The little one even wets himself because of it. Many of our friends have already been wounded or killed.”

As Ilin notes in his description of the work, “These stories were collected by a friend who joined a network of volunteers and hosted many refugee families transiting through Russia to Europe in their apartment in Saint Petersburg.” As such, these accounts radiate through the social body of a contemporary society that looks away from war, but nonetheless, is dying from its effects.

Alexandro Segade is an interdisciplinary artist whose queer world-building projects propose speculative group identities.

Past Exhibition

Misha Ilin’s body of work asserts that ecocide, wars, body politics, and capital each exist as a sort of radioactive event, altering the genome of “reality.”…