Past Exhibition

Gold Rush

Working with core samples extracted from a mine on unceded Passamaquoddy land in Maine, Stephanie Garon explores notions of labor, permanence, and land claim.

Stephanie Garon is uniquely prepared to mine the residue and history of a spurious “gold rush,” in northern Maine, of all places. I’ve been to Maine every summer of my octogenarian life and until two years ago I had no idea that mining was a factor in the state’s environmental history. Garon is an eco-artist with a science degree from Cornell and a deep commitment to research on nature’s side. In June 2021 she responded to a juried call and was invited to Smithereen Farm to make art about the Greenhorns’ extensive activities in Pembroke, on Cobscook Bay in Downeast Maine, close to the Canadian border. Founder and leader Severine von Tschering Fleming has acquired a number of properties in the town and the area, concentrating on environmental, agricultural, and economic restoration. The high (or low) point of Garon’s visit was her descent into a damp basement room where shelves of 20,000 core samples have been stored for a century.

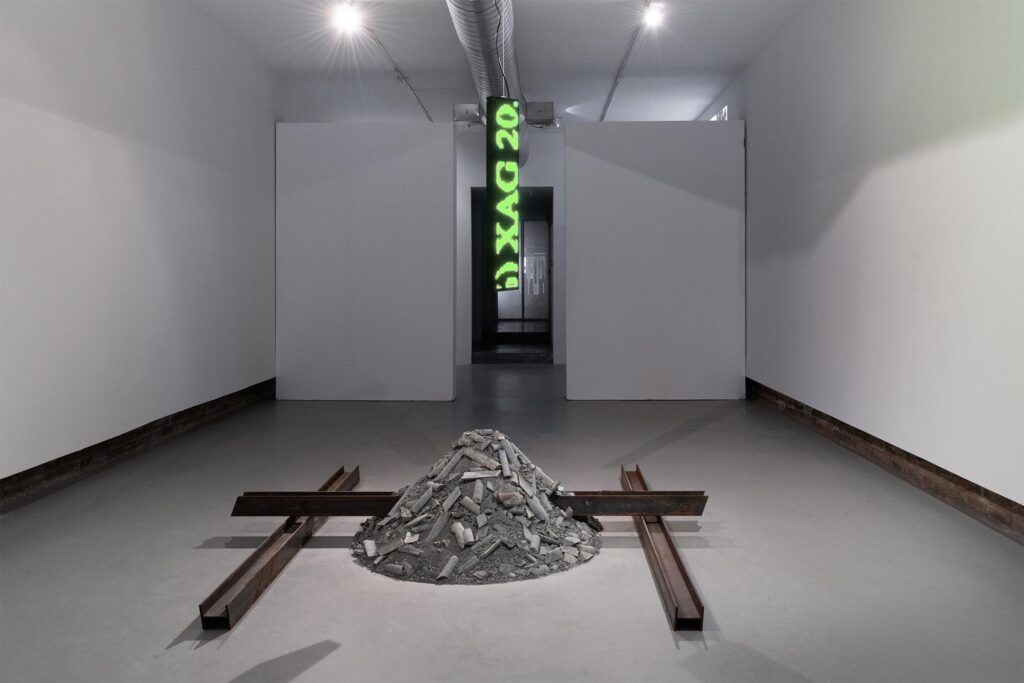

Geology is literally the ground for this multilayered show, which incorporates a number of issues: art, of course, as well as land use, history, cultural colonialism, indigenous rights and environmental justice. There is a doubly local context here, as noted in a review of the initial show: “Garon’s large-scale drawings and crushed rock core paintings on view incorporate DC tap water and chemicals used in mining, situating the work locally.” The handsome and varied sculptures, the crushed rock paintings and drawings, stand on their own, offering a powerful esthetic glimpse of the endless gifts and uses of rock, which is also an endless source of visual pleasure in itself.

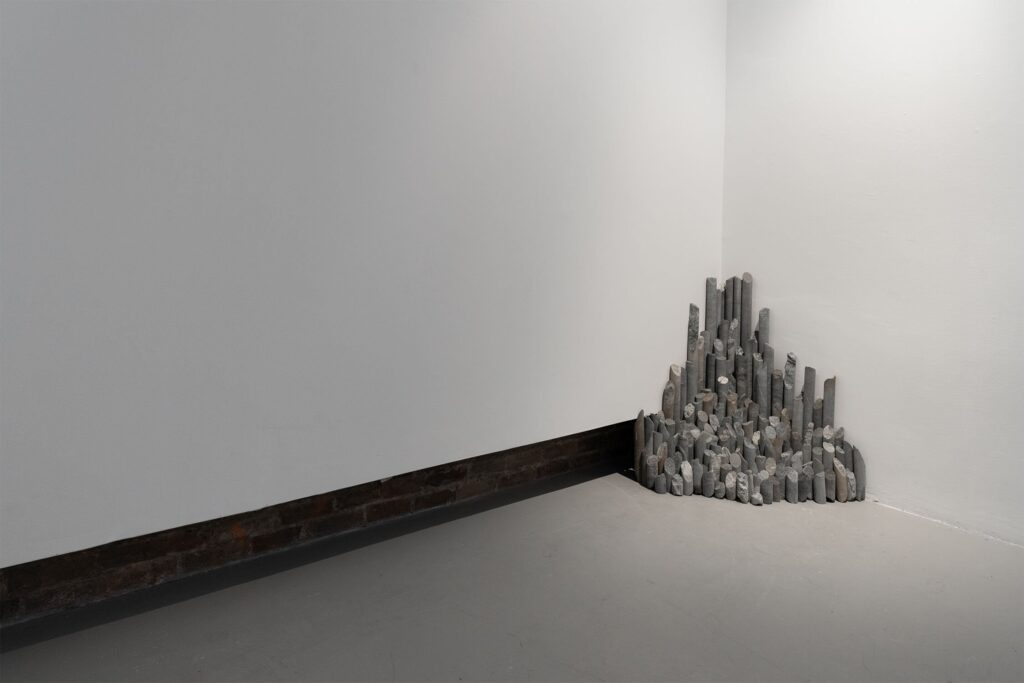

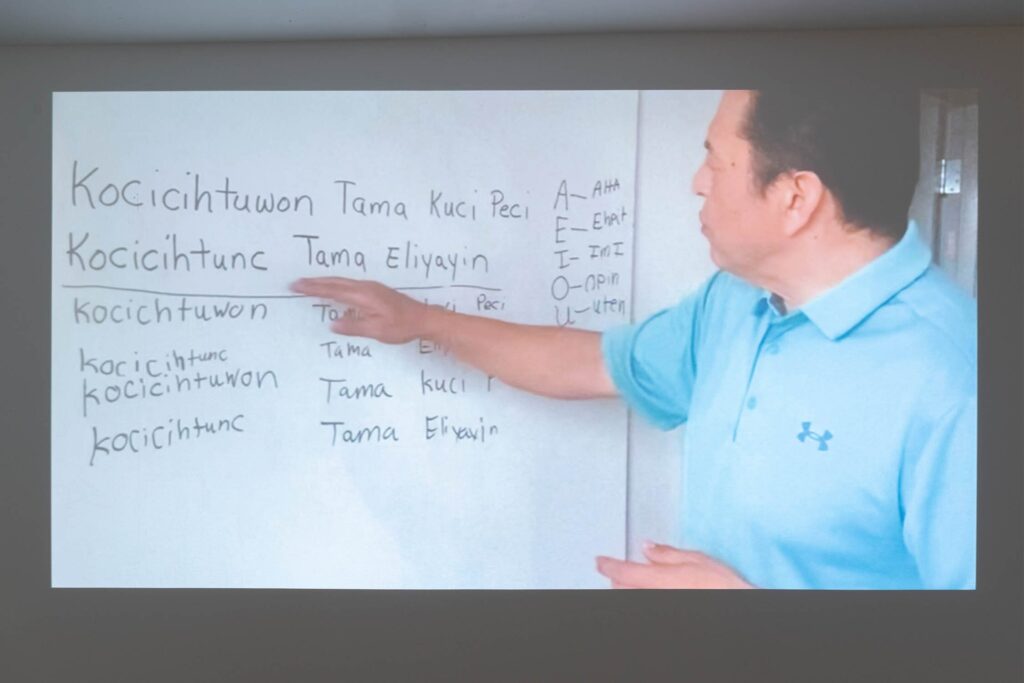

But art is only the first layer of such a sedimented project. One of the quieter works Formation (2022) speaks to the heart of the exhibition: several unprepossessing gray rock cores from Pembroke’s Big Hill mine huddle in a corner. They are the products of determined, if unsuccessful, speculation over decades. The punctured field from which they were taken is shown in the video, which includes voiceovers from concerned citizens, including a local clamdigger (who mentions that he built his house with his clamming income; it only took 12 years to pay back the loan), and Sipayik Museum Director Dwayne Tomah, who emphasizes the values of the ancient indigenous cultures of the Abenaki–Penobscot–Maliseet tribes, defending Indigenous traditions that rely on the health of the region’s ecosystems. Their efforts to curtail mining in the area has paralleled the local grassroots campaigns warning that Maine was the new Wild West for greedy foreign corporations and opposing the misplaced values of our society’s mainstream.

The notion of a gold rush refers not only to the mid-nineteenth century California–Alaska gold rushes but to the overall money-madness of our current society, crypto currencies, and other schemes. Money talks, money tempts, money rules, and money madness often destroys both land and lives. Garon is concerned with the commodification of nature, hoping that her work will spark “dialogue about how we use our natural resources and what our own personal connections to them are.” In her central installation, local mining history and contemporary art (also a commodity) are put into unexpected context by a stock ticker recording the fluctuating prices for gold, silver, and copper. Viewers with cell phones are invited to assess the economic values of the traces of minerals in the cores.

The combined efforts of local and statewide grassroots campaigns to restrict mining have proved successful. Community action groups, among them Friends of Cobscook Bay, Resist Mining in Maine, and the Pine Tree Amendment, have exposed the adverse effects of mineral mining on air, wildlife, and drinking water. I had the chance to participate in one event in 2021, when the energy was building. Maine is a poor state, so for decades mining dangled hope over its northern region, which does not share in the tourism and luxury getaways of the coastal areas. That hope is long gone, unless the discovery of lucrative lithium deposits changes the laws; in 2022, the town of Pembroke passed an ordinance, halting attempts at large-scale silver mining at Big Hill and Picket Mountain by a Canadian corporation.

Garon’s multimedia show, now traveling, is an innovative and relatively new expansion of context and content which could have stood on its own as art as art, but Garon has taken on a far deeper task with art that can be amplified by its sources, market, and cultural impact—both negative and positive. In doing so she joins the burgeoning band of artmakers who have entered the fray for a healthy environment.

Lucy Lippard is a feminist art critic and activist.

Past Exhibition

Working with core samples extracted from a mine on unceded Passamaquoddy land in Maine, Stephanie Garon explores notions of labor, permanence, and land claim.