Past Exhibition

When Tomorrow Arrives We Will Love Life

Abed Elmajid Shalabi’s exhibition presents new works that confront the realities of modernization in the post-oil Arab world.

Abed Elmajid Shalabi’s When Tomorrow Arrives We Love Life comprises nine elegant, spare sculptures installed at irregular intervals throughout the Hamiltonian Artists space. Each sculpture riffs on car culture and is made from a cast or literal piece of a car or truck. Gas nozzles, road signs, a truck bed, or car seats repeat throughout, but not as abstract motifs; these are actual objects synonymous with distances, journeys, and travel, which are the exhibition’s implicit themes. For Shalabi, the exhibition considers a post-oil future of the Arab world, a time at which we have yet to arrive. This anticipation is only heightened by his placement of each piece at an expanse from each other, creating a cohesive installation that hinges on distance, literally and figuratively.

The first work encountered in the installation is Passenger Seat (2024), a concrete cast of a car seat’s back cushion upside down with its headrest separated. Placed directly on the floor, a white glazed ceramic with holes punched through is placed on its top, and a severed lead pipe is laid vertically down its middle. The seams of the seat’s cast are rough-hewn, which slyly contorts time in this work as well as throughout the exhibition; the seat feels contemporary, but its craggy edges make it feel more like a ruin. One end of the pipe has a similarly riven tip as if it’s a piece pulled off of a larger whole.

The tip points away from the exhibition’s second work, the wall-mounted Nozzle Connector (2024), a glazed ceramic tube stretching out from the wall like a bent finger. Closer examination reveals its geometric angles and edges, much neater than Passenger Seat, but the hole at its nozzle is nevertheless cleft. This slight detail connects both pieces formally, enabling material and conceptual relationships to coalesce naturally through the gap between them. In other words, such thematic connections only emerge for the viewer as they proceed through the exhibition. Travel is necessary.

Between spaces–and the possibilities they present–are of particular interest to Shalabi. Gas stations are one such space for him, and he worked at one after arriving in the US from Israel–Palestine, where he grew up in a Muslim family who are Palestinian citizens of Israel. Pumping gas, he saw how people of all backgrounds intermixed at the station as they all needed gas for their cars. He also observed the bravado of American car culture for the first time, with the macho-ness of big trucks or the flash of a particular status car. They all needed gas to go about their daily lives. They were therefore all dependent on oil, the economic driver of the Arab world. However, the cost of oil didn’t enrich the lives of everyday Arabs like Shalabi’s family. There was a gap between the shallow excess of car culture, oil’s financial value, and the realities of people who lived on top of petroleum.

Though Shalabi wants people to consider “the gas station experience,” their relationship to oil, and an Arab future that isn’t dependent on the globe’s reliance on it, he also asserts that his personal stories aren’t part of the work. Instead, the work is about material transformation–how one thing can become another–through his own catalytic transformation of familiar objects into casts of themselves or assemblage of found materials into something entirely new. In this way, Shalabi figuratively recasts a physical, real thing–such as a car seat–into something reimagined. This is a process akin to those of poets like Mahmoud Darwish, from which the exhibition takes its title. Considered Palestine’s national poet, Darwish was an activist for peace who wrote the Palestinian Declaration of Independence. For Shalabi, poets and activists of Darwish’s generation represented and articulated the dreams of a future Arab world that the current world still needs to achieve.

Shalabi transforms and distorts materials poetically, but his visual language relies less on abstraction than the tangible. Throughout much of the exhibition, he uses just one cast of a car seat, but his play with color, texture, and material juxtaposition reenvisions this singular seat or rhythmic inclusion of black piping. Beyond the wall Nozzle Connector is Two Hundred Ninety-Seven Holes (2024) which picks up the thread of the pipe at its center bottom. A silvery iridescent sign typically found on highways is placed on the top edge of this black tubular form; at the top is a ceramic surface with the bumpy texture of an industrial anti-slip mat. This sign is placed on top of another road sign, a pearly white one with black edging, four bolts, and a single screw placed perpendicularly beneath it.

These literal signs in turn don’t communicate any message, and as the viewer peers down to examine both signs, only the juxtaposition of material and the textures therein are visible. For instance, in place of written language, the silver sign is just a surface of slashy, gestural texture that only conveys the intrinsic material properties of the sign instead of any symbol.

Stacking abstract times and histories as well as formal lines and planes is an aesthetic tactic Shalabi uses to invert and distort symbols and the signified so that the viewer can make their own meaning. Past Two Hundred and Nine-Seven Holes the exhibition crescendos with the remaining six works, all of which similarly stack objects or symbols in a reconfiguration of the familiar into eerie relics of some timeless age. They are too identifiable to be of the past, their surfaces too worked to be pristinely futuristic, and yet too distorted to be of the present. The past, future, and present are a stack, and this timelessness imbues all these works with an elegiac quality. For instance, in Two Seats, Two Buckets (2024), two identical seats in bright yellow ceramic sit atop a used utility bucket and paint can, respectively. With an industrial sheen, the one atop the utility bucket is perched higher than that of the paint can (perhaps denoting a parent and child?). Both seats face the middle of the room as if they are for a phantom driver and passenger headed for the center of the exhibition.

There, Shalabi has placed the most enigmatic work on view here, the straight-forwardly titled Truck Bed (2024). Hovering just off the floor, this fiberglass-reinforced cement cast of the middle portions of a truck bed is precariously stabilized by the orange 5-gallon Home Depot bucket at its topside, where the cast reaches up into a wheel well. In the middle of the ridged bed pokes a nozzle (a bent pipe form), its beak uselessly and vainly reaching for something. Inside the bucket is an ambiguous material in solid white, the weight of which keeps the whole structure upright. The juxtaposition of the filled bucket and the nozzle with nothing to fill, enhances the feeling of striving for, but never accomplishing; dreaming, but never attaining.

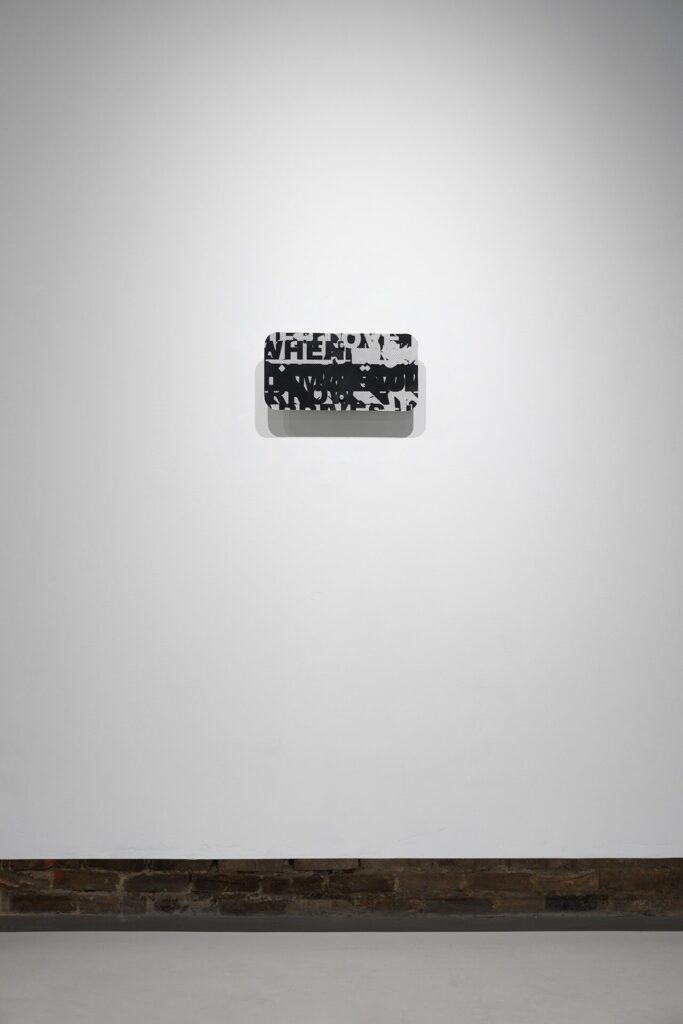

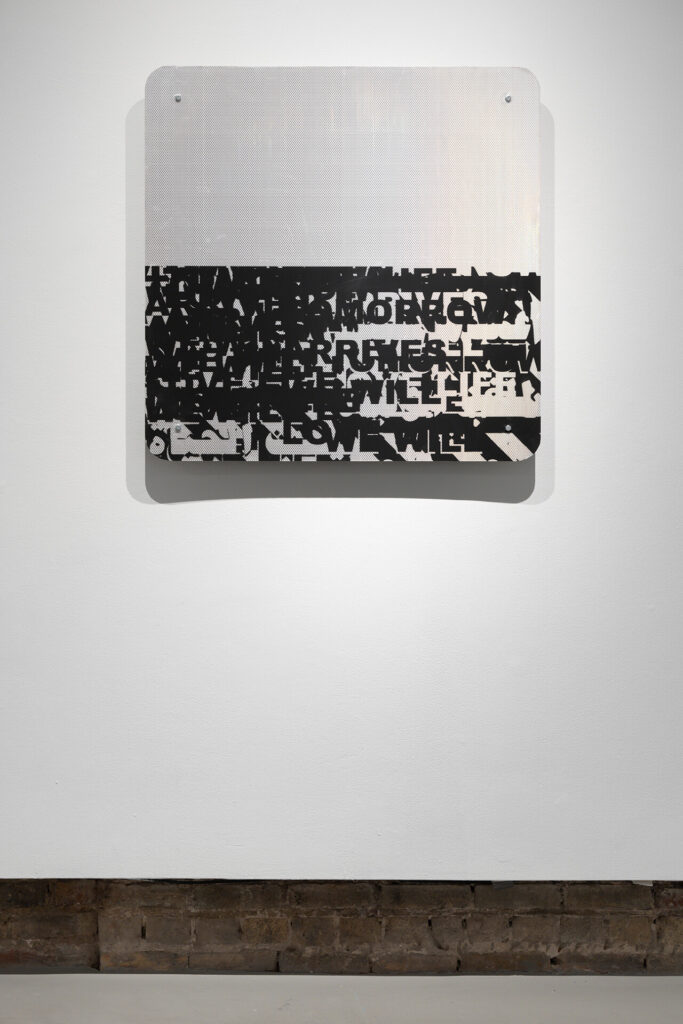

Endlessly endeavoring (which inherently means always trying, going, never stopping) is the prevailing sentiment of Darwish’s A State of Siege (2002), the poem from which Shalabi takes his title. This verse is written in Latin and Arabic along two custom-made road signs entitled When, Love (2024) and Love, Will, Life (2024). Words, like “Arrives” and “When,” are extracted, replicated, and repeated in big black and white industrial-looking letters so much that they become almost illegible. But only almost, as these words connoting journey and time are distinct from the otherwise indistinguishable mass of words. These words, along with “Love,” are clearly discernible only as empty gaps between layers and layers of letters. The viewer can see these letters only in context with their indecipherable stacks. As with the installation as a whole, the distance between things is everything.

Leah Triplett Harrington is director of exhibitions and contemporary curatorial initiatives at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts

Past Exhibition

Abed Elmajid Shalabi’s exhibition presents new works that confront the realities of modernization in the post-oil Arab world.