Past Exhibition

Sticky Gum Flat

Curated by artist Ali Kaeini, this group exhibition reflects and responds to the notion of “street life.” Featuring artists Ian Ha, Jung Won Lee, Alexis Mabry, Farah Mohammad, Paz Sher, and Lulu White.…

It is not difficult to imagine a world abandoned, for we have willingly abandoned so much already: our responsibility to nature, to higher education, and to public health; the legal and human rights of those fleeing oppression; vigilance against fascism and genocide; collective desire to hold the rich and powerful to account. With every student protester and immigrant kidnapped by ICE and transported to prisons in Louisiana and El Salvador without due process—funneled into incarceration pipelines built upon the infrastructures of surveillance, enslavement, and colonialism—this administration continues its war of retribution on dissenters of all kinds. There can be no ideals of free inquiry and free speech without a responsibility to free people. And so, here we are. Few images can meet these concatenating terrors.

And yet, protest continues. Public spaces, large and small, urban and rural, continue to serve as venues for resistance against institutional orders, with each act of defiance a small strike against repositories of cultural and political hegemony. People of all backgrounds and political frameworks continue to organize and gather, placing their bodies on the line to refuse the human impulse to freeze or appease. But the sweeping scope of institutionalized retaliation across sectors and communities has shifted the threat landscape for a broad swathe of Americans almost overnight. “Institutions [and cultural groups] that have mostly felt themselves protected from political retaliation now find themselves feeling some of the vulnerability that marginalized communities have long felt.”1 But it has been helpful to me to remember that artists (at least some of them) form an important part of the constellation of defiance against tyrannies of all kinds. Artist’s engagement in critique and provocation continues the important legacy of nonviolent action, namely, the mobilization of conceptual imagery to slow or re-route the forces of accommodation that render catastrophe digestible.

However, in a world shaped by continual crises, terror, and shock—conditions that the Right has appropriated from the historical avant-garde and leftist political strategies—art that engages slowness, patience, and subtlety feels more viable these days. This slower, more subtle tempo seems to be at work in the exhibition “Sticky Gum Flat,” curated by Ali Kaeni, and featuring an assembly of works by artists Ian Ha, Jung Won Lee, Alexis Mabry, Farah Mohammad, Paz Sher, and Lulu White. A heterogeneous admixture of sculptural strategies, “Sticky Gum Flat” holds together a constellation of practices to point to the “possibilities of the street,” thereby unfurling the question of who and what occupies space in politically volatile times.2

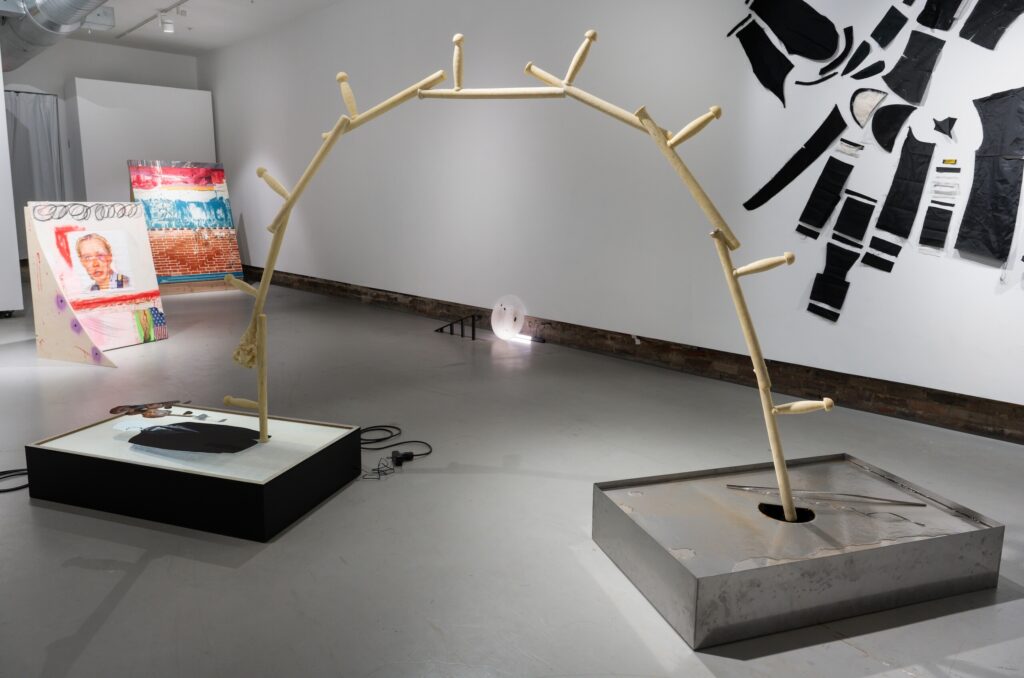

The sculptural shape of this exhibition, peppered with works falling in and out of two- and three- dimensional space, holds the heart of this exhibition. Artist use a variety of means to slur and slip questions of apportioned space, where things belong, and what feels extraneous or out of bounds. Upon entering, Jung Wong Lee’s metal work “Slow as a Knock, Bold as a Silence” (2025) forms an uncomfortable first note at the front of the gallery, its simple curvature a docile reminder of the metal rail’s utility as a crowd barrier used to kettle and organize crowds in the margins of streets or at the edge of stages. (Fig. 1) Whether Lee’s fragmented crowd architecture holds the forces of celebration or protest is left to the viewer to decide, but it is hard not to see the two browning tree leaves crushed in between the seams of the metal frame as anything other than instantiations of life pressed against the frameworks of power. A colorful, heterogenous notion of collective life, presented in proximity to Lee’s sculpture, is Farah Mohammad’s epic “Loving in Fragments” (2025), which uses multiple printmaking techniques to emphasize embodied negotiations of space, both physical and emotional. (Fig. 2) Urban architectural landscapes formed of leaking, drippy washes of color, gathered together by margins of distance, people-less corridors, and disorienting perspective ask the viewer to question where they stand in relationship to this space, and to imagine a world unfixed. Whether the possibilities of that imagining are dark or liberatory is unclear, but what does shine through are the capacities of Mohammad’s media to unfurl the role of public space as a terrain of obstacles both seen and felt, layered and transparent—a shining counterpart to Lee’s work and the works of Lulu White, whose textured surfaces composed of dryer lint and epoxy ask questions using the metaphors of mirrors and x-ray perspective to question what can be seen, missed, invisible, just under the surface.

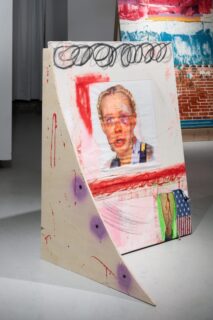

After these reverberant notes beginning the exhibition, things get trickier for the viewer. Narrow pathways provide little space to step back and confront larger scale installations and wall works set further back into the gallery. Nothing can be addressed completely (meaning confrontationally), which renders the tone of the exhibition crowded and crushed—perhaps unintentional, but nevertheless useful to the curator’s emphasis on underscoring the complexity of our present. Ian Ha and Alexis Mabry form a unique alliance due to the formal similarities and proximity of their work; the use of board and plywood to push the two-dimensional into the third and offer a transition from Mohammad’s fractured urban environs into the collageaic world of Ha’s graffitied walls and Mabry’s skate park ramps. (Fig. 3, 4) Even a desire for more space to allow these works to shout and sing is perhaps impossible in “these times”—the competition for space, real and imagined, is undoubtedly on the mind of these two artists, who emphasize the contested and multivocal nature of living in community with one’s surroundings, and the triumphs and wounds that are left as marks on space and body along the way. Blood smears, spray marks, coiling wire, bruised flesh, a palimpsest of consequences accumulate.

And yet, it is the smaller, quieter works placed at the margins of the gallery that form the most powerful, poignant moments in this presentation. Less flat, more sticky in their responses to the world outside, Paz Sher’s sharp expression of the horrors unfolding in Palestine—a ballpoint pen oriented from West to East, symbol of literacy and communication turned to missile, pinning (striking) an olive seed to the wall—refuses to ignore a genocide (and perhaps, the role of Western powers within it), even as our (art)world carries on (Fig. 6), while Lee’s “Morning Comfort” (2025) sketch of a ladder perched in the rafters asks us to imagine an escape route out, or the impossibility or ethical problematics of creating one. A powerful conclusion to an exhibition that does not abandon the world but invites it in, in fragments.

–Dr. Jordan Amirkhani, June 5, 2025

Past Exhibition

Curated by artist Ali Kaeini, this group exhibition reflects and responds to the notion of “street life.” Featuring artists Ian Ha, Jung Won Lee, Alexis Mabry, Farah Mohammad, Paz Sher, and Lulu White.…